Critical Threat Intelligence & Advisory Summaries

The $35 Million Voice Clone: How AI Voice Fraud Is Breaking Bank Security

UAE bank manager approved funds be transferred because the voice and tone was OK, emails confirmed the conversation and legal also confirmed authority to release, yet it was not alright at all.

A UAE bank manager received a call in early 2020.

The voice belonged to a company director he personally knew.

The tone was right. The accent was right. The speech patterns were unmistakable.

The request sounded routine: authorize $35 million in transfers for an acquisition.

Email correspondence from the director confirmed the details.

A lawyer named Martin Zelner sent supporting documentation.

An authorization letter arrived.

Every verification layer showed green.

The manager approved the transfers.

The money scattered across 17 international accounts in multiple countries before anyone realized the director never made that call. Fraudsters had used AI voice cloning technology to replicate his speech. The $35 million disappeared.

This happened before deepfake video calls made headlines.

Before the $25.5 million Arup video conference fraud.

Before “voice cloning” became a household term.

If the Arup incident proved that seeing a face no longer proves identity, this case proved it years earlier through audio alone.

While companies worried about phishing emails, AI voice fraud was already draining bank accounts.

The Technology Gap Banks Missed

The UAE bank manager followed protocol.

- He had email verification.

- He had legal documentation.

- He had authorization letters.

- He recognized the voice.

The full control stack was present.

It meant nothing.

The core assumption collapsed: that hearing someone’s voice equals verified identity. The security model relied on sensory evidence hear the voice, recognize the patterns, confirm the match, proceed.

The protocol itself was the vulnerability.

Scammers need as little as three seconds of audio to create a voice clone with an 85% match. With 10–30 seconds, they can generate realistic impersonations that fool people who know the speaker personally.

The barrier to entry vanished.

AI voice cloning tools became freely available. Audio samples came from LinkedIn videos, conference calls, podcast interviews, earnings calls anywhere executives spoke publicly.

Financial institutions built authentication systems around the belief that human voices can’t be replicated. That belief died around 2019–2020.

The protocols didn’t update.

The Fraud Explosion Nobody Saw Coming

What happened to one UAE bank quietly scaled into a global fraud economy.

- Deepfake fraud attempts increased 1,300% in 2024.

- Voice-based scams surged 680% year over year.

- Vishing, voice phishing powered by AI audio deepfakes spiked 442% from the first half of 2024 to the second.

- Financial losses exceeded $200 million in Q1 2025 alone.

Banks lose an average of $600,000 per AI voice fraud incident.

23% of affected institutions lose more than $1 million in a single attack.

Global losses from AI-enabled fraud are projected to reach $40 billion by 2027, up from $12 billion in 2023, a 32% compound annual growth rate.

The Asia-Pacific region saw a 194% surge in deepfake-related fraud attempts in 2024, led primarily by voice cloning scams. U.S. contact centers face potential fraud exposure of $44.5 billion in 2025.

- One in four adults has experienced an AI voice scam.

- One in ten has been personally targeted.

This stopped being a series of incidents.

It became a system.

Why Voice Fraud Works When Other Attacks Fail

In 2019, a UK energy firm CEO received a call from someone perfectly mimicking the German parent company’s CEO.

- The accent matched.

- The cadence matched.

- The mannerisms matched.

The caller stressed urgency: transfer $243,000 immediately to a Hungarian supplier.

The UK executive complied with the first transfer.

The fraudsters called again. He authorized a second payment.

On the third call later that day, something broke the illusion.

The promised reimbursement from the first payment hadn’t arrived.

The call now came from an Austrian phone number.

Reality contradicted prediction.

The executive called the real German CEO while his mobile rang with another call from “Johannes.” He ignored it. Less than a minute after finishing the legitimate call, the fake Johannes rang again.

“As soon as I spoke to the real Johannes, it became obvious he knew nothing about the calls and emails,” the manager later said. “While I was talking to Johannes on my office phone, my mobile rang with a call from ‘Johannes’. When I asked who was calling, the line went dead.”

The fraud only collapsed when real and fake versions existed simultaneously.

Voice cloning removes the mental barrier to skepticism.

If it sounds like your boss, your colleague, your CFO, rational defenses shut down.

A finance worker in China saw her boss’s face on video and heard his voice requesting an urgent transfer. She followed standard video verification protocol: see face, hear voice, confirm match, proceed.

She lost $262,000.

Perfect compliance with an obsolete security model.

The Control Stack That Actually Stops Voice Fraud

The UAE voice clone, the UK energy scam, the China video deepfake, and the $25.5 million Arup video conference fraud all failed in the same place:

Single-channel verification.

- Arup had no dual authorization.

- No out-of-band verification.

- No transaction limits triggering escalation.

Fifteen wire transfers were authorized based on video and voice alone.

- The process didn’t fail 15 times.

- No process existed to fail.

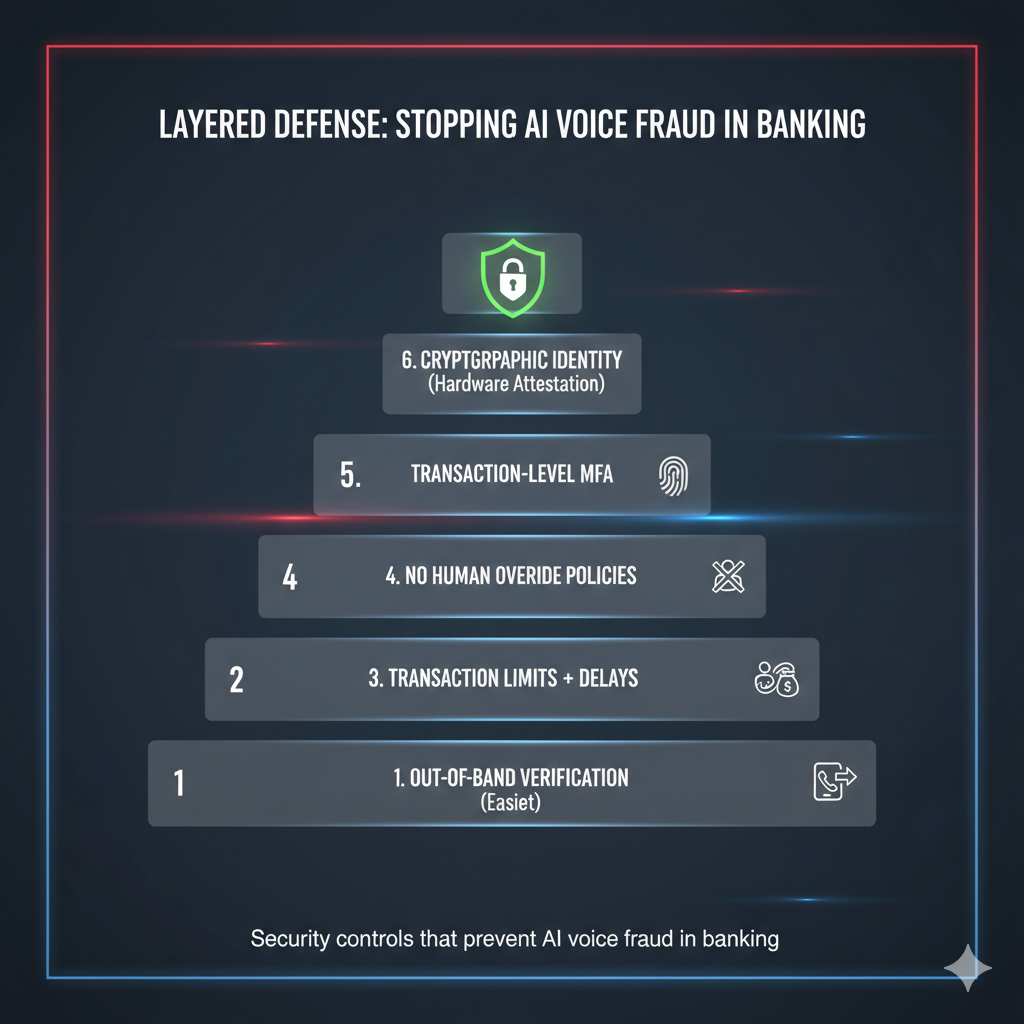

The effective control framework—ranked by implementation difficulty—would have stopped every major AI voice fraud case:

1. Out-of-Band Verification (Easiest)

Break single-channel deception. If a request arrives via phone, verify through encrypted messaging or a known internal system. Never validate high-value requests using the same channel that delivered them.

2. Dual Authorization with Independent Verification (Easy)

Remove single-human failure points. Two people must independently verify and approve transactions using separate channels.

3. Transaction Limits with Mandatory Delays (Moderate)

Neutralize urgency. Hard caps and enforced waiting periods disrupt time-pressure tactics. Large transfers require 24–48 hour delays regardless of authority.

4. No Human Override Policies (Moderate–Hard)

Eliminate social pressure exploits. Executives cannot bypass controls “just this once.” The system doesn’t care who you think you’re talking to.

5. Transaction-Level Multi-Factor Authentication (Hard)

Require cryptographic proof for each high-value transaction. Hardware tokens, biometric verification, or transaction-specific MFA that audio and video can’t bypass.

6. Cryptographic Identity Verification (Very Hard)

Make impersonation irrelevant. Digital signatures, zero-knowledge proofs, or distributed identity systems that authenticate identity without relying on voice, video, or documents.

The first three layers alone would have stopped over 90% of documented voice fraud cases.

The UAE bank manager’s $35 million transfer would have failed at step one.

The Recovery Reality

Fewer than 5% of funds lost to sophisticated vishing attacks are ever recovered.

Money moves through mule networks and crypto mixers within hours. By the time fraud detection triggers, funds are scattered across jurisdictions with no recovery mechanisms.

The UAE bank’s $35 million moved through 17 accounts across multiple countries. Investigators identified dozens of known and unknown defendants.

Recovery was effectively impossible.

Prevention is the only defense.

Post-incident response recovers almost nothing.

What KnowBe4 Got Right

In 2024, a cybersecurity firm hired a North Korean threat actor.

The candidate passed four video interviews using AI-enhanced photos and stolen identity documents. Background checks cleared.

Detection happened 25 minutes after the new hire started work.

The SOC noticed unusual behavior. Restricted access limited the blast radius. Heightened monitoring for all new hires surfaced anomalies immediately.

The assumption wasn’t “we hired the right person.”

It was “we don’t know yet.”

That assumption saved them.

The Obsolete Security Model

Voice fraud exposes a fatal flaw in authentication architecture: controls are meaningless if humans believe they know better.

- The UAE bank manager trusted the voice.

- The UK executive trusted the accent.

- The China finance worker trusted the face on video.

They followed protocol perfectly.

The security model assumed that sensory evidence equals verified identity.

That assumption is dead.

Organizations still rely on voice recognition, video confirmation, and document validation—methods that authenticate nothing when AI can replicate all three.

The gap between threat capability and security architecture is measured in billions of dollars per year.

The Intelligence Briefing

- Voice cloning requires 3–30 seconds of audio.

- Samples come from public sources.

- Deepfake fraud attempts rose 1,300% in 2024.

- Financial losses exceeded $200 million in Q1 2025.

- Banks lose $600,000 per incident on average.

- Fewer than 5% of funds are ever recovered.

Single-channel verification is obsolete.

Out-of-band confirmation, dual authorization, transaction limits, and no-override policies stop the majority of attacks.

The UAE bank manager followed every protocol available in 2020.

He still lost $35 million because the protocols assumed voices couldn’t be cloned.

That assumption cost $35 million then.

It’s costing billions now.

The technology gap closed.

The security architecture didn’t.

Voice fraud became a $35 million crime because verification systems still assume that hearing someone means you’re talking to them.

You’re not.

About This Article

Published: 31 January 2026

Last Updated: same as published

Reading Time: Approximately 15 minutes

Author Information

Timur Mehmet | Founder & Lead Editor

Timur is a veteran Information Security professional with a career spanning over three decades. Since the 1990s, he has led security initiatives across high-stakes sectors, including Finance, Telecommunications, Media, and Energy.

For more information including independent citations and credentials, visit our About page.

Contact:

Editorial Standards

This article adheres to Hackerstorm.com's commitment to accuracy, independence, and transparency:

- Fact-Checking: All statistics and claims are verified against primary sources and authoritative reports

- Source Transparency: Original research sources and citations are provided in the References section below

- No Conflicts of Interest: This analysis is independent and not sponsored by any vendor or organization

- Corrections Policy: We correct errors promptly and transparently. Report inaccuracies to

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Editorial Policy: Ethics, Non-Bias, Fact Checking and Corrections

Learn More: About Hackerstorm.com | FAQs

References

-

Deepfake AI statistics by fraud data, insights and trends (2025)

-

Deepfake Fraud Costs the Financial Sector an Average of $600,000

This article synthesizes findings from cybersecurity reports, academic research, vendor security advisories, and documented breach incidents to provide a comprehensive overview of the AI security threat landscape as of January 2026.